We Don't Have to Wait 40 Years to Do The Right Thing

By now, I thought everyone knew the story of Ignaz Semmelweis, the doctor who tried to get his colleagues to wash their hands in the 1840s. Not only did they refuse to listen, they decided he was crazy.

They had him committed to an asylum.

He died there.

Semmelweis understood the basics of disease transmissions 20 years before Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch confirmed germ theory. He started with a simple problem. There were two maternity clinics at the hospital where he worked. Pregnant women used to get down on their knees and beg for the second clinic. Going to the first clinic was considered a death sentence. Women literally preferred to give birth in the streets, and they did.

Semmelweis followed the data.

Giving birth in the streets was safer. If you went to the first clinic, there was a high chance you'd die from puerperal fever.

Then something else happened.

Semmelweis lost one of his best friends, a physician who died from an infection after getting poked by a dirty scalpal. That helped him realize what was going on. The first clinic was run by doctors who were doing lots of other things, including autopsies, before they delivered babies. The second clinic was run by midwives, who rarely if ever touched dead people.

Semmelweiss scratched his chin.

"Maybe it's the corpses."

(I'm dramatizing.)

He decided to see. He made doctors at the first clinic wash their hands with a chlorinated lime solution. They didn't complain. They just did it. Sure enough, maternal mortality dropped by 90 percent. Semmelweis had solved the problem while laying the foundation of hospital sanitation.

He was a hero, but that's not how he was treated.

The medical community in Vienna didn't just shrug him off. They made fun of him. They came up with excuses for rejecting his findings. They didn't even run their own trials to see if he was right. Some doctors declared it was blasphemy to suggest that gentlemen like themselves could have unclean hands, even if they'd been working around corpses all day.

They started harassing him.

Semmelweis didn't back down. He became outspoken. The indifference of the medical community outraged him. Eventually, he started accusing his colleagues of murder. Of course, he was right. It didn't matter. Politics and prejudice prevailed over reason, even at hospitals.

In the end, he lost his job.

His friends and colleagues insisted he was going crazy. They eventually convinced his wife to have him committed. Barely two weeks later, the guards there beat him so badly that he died of septic shock.

It's quite a story.

It left such a mark on medical historians and psychologists that they coined a term to describe what happened, and they named it after him. When an entire society or profession rejects new information and chooses to hug outdated norms, they're demonstrating the Semmelweis Reflex.

You'd think this story would give the current generation of doctors a sense of humility. Their predecessors didn't think it was important to wash their hands. They were so confident about it that they didn't listen to anyone, not even one of their own when he showed them clear evidence.

Instead, they complained about his tone.

They bullied him.

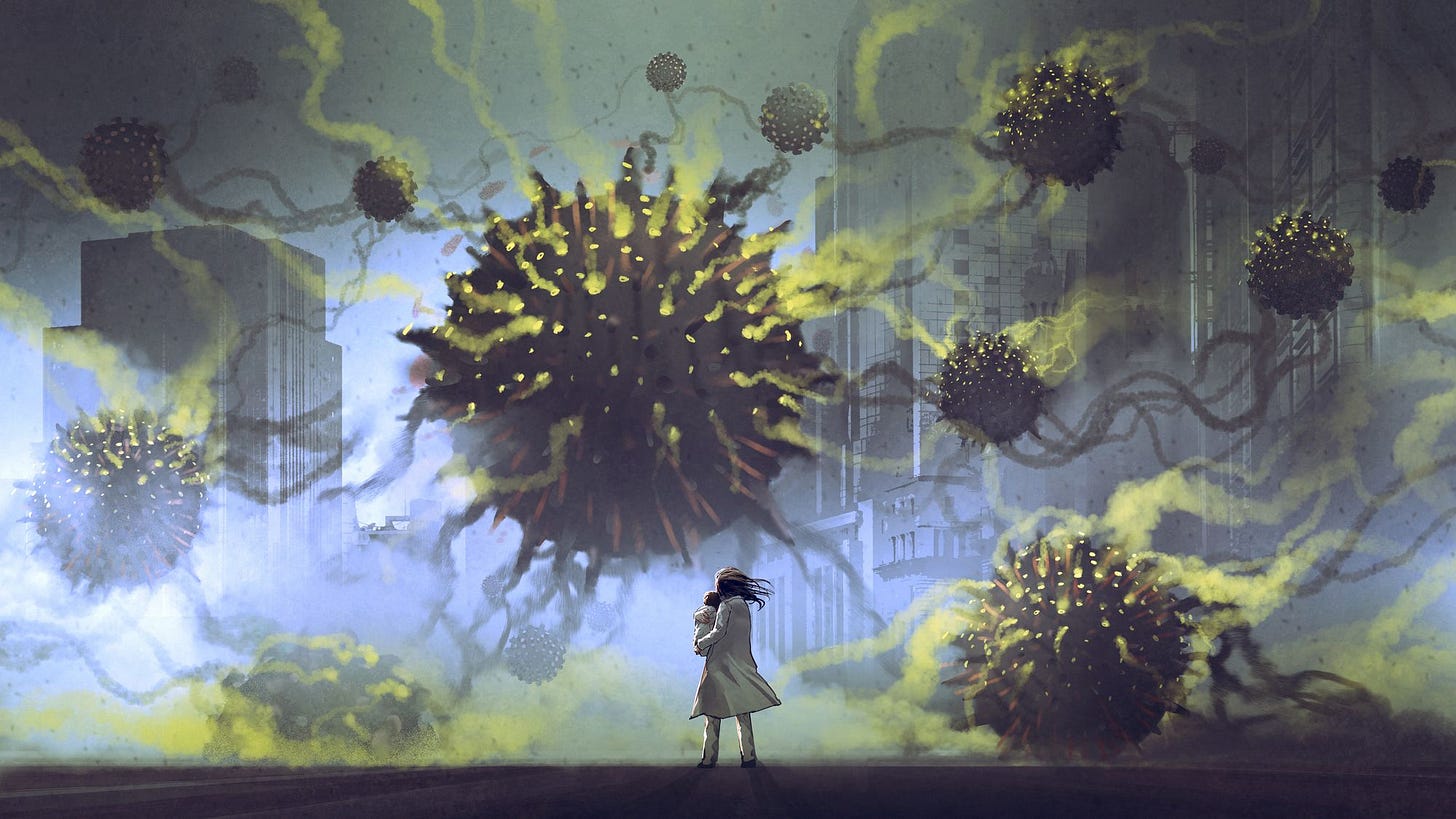

Nearly 200 years later, we're making the exact same mistakes as a society. We have overwhelming evidence that viruses spread through the air and via surfaces. And yet our public health institutions intentionally leave masks and clean air out of their recommendations. It doesn't matter whether we're talking about protecting ourselves from viruses or wildfire smoke.

Meanwhile, these same institutions sit back and watch as wellness grifters and corrupt doctors suggest that anyone who wears a mask or uses HEPA filters is suffering from some kind of anxiety.

This decade will go down in history as a time when doctors and healthcare officials had a chance to avoid repeating history. Right now, they have a chance to save lives and protect people's health.

They won't even say the words.

It's embarrassing.

Semmelweiss introduced the idea of handwashing in 1847. It took forty years to finally become commonplace in healthcare settings. Now our healthcare officials talk about handwashing, but they won't talk about any of the other protections we could be taking to avoid airborne diseases.

They gaslight anyone who disagrees.

We even see some doctors engaging in the exact same bullying that killed Semmelweis. These doctors brag about treating patients without wearing masks, as if their smiles alone can cure disease. They might as well brag about not washing their hands after handling a corpse.

We don't have to wait 40 years to do the right thing.

We could do it now.