Everyone Just Wants to Forget: The Power of Collective Amnesia

Most people are more than willing to forget the past, along with its important lessons.

We all have things we want to forget.

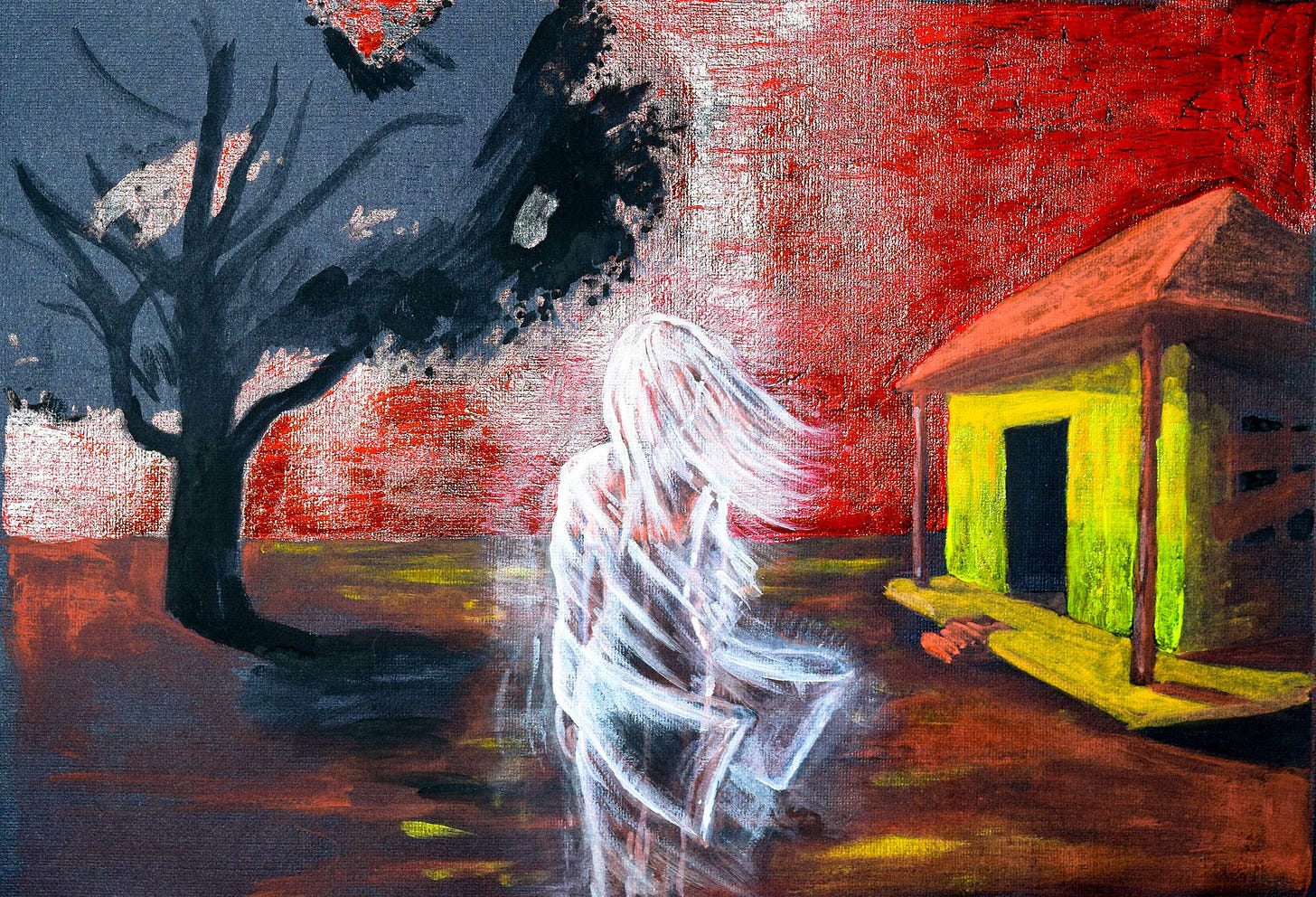

Maybe it's a bad date. Maybe it's an abusive childhood. Maybe it's a year spent locked up in your house, thinking about death.

Maybe it's all three.

Some of us do a balancing act between forgetting and remembering. In order to get through the day, I have to forget my teen years, and a lot of my 20s too. We're talking about things that left me choking back tears in front of police officers, or lying to social workers when I got called out of class to answer squirmy questions. But I also have to remember. All those painful memories contain valuable lessons. They contain the baseline code of who I am.

I force myself to relive them.

Pain is a great teacher.

Those memories often explain why you feel sad or angry for no apparent reason, or why you do things that don't make sense on the surface.

A lot of people don't see the world like that. They just want to forget. They think it'll make them happy. They want to pretend the past never happened, especially if they were the one causing someone else pain. You can push bad memories down into the sewer of your mind. Your body never forgets. It carries the raw, unprocessed pain around with it.

That's how a lot of broken souls get by these days, stuffing down traumatic memories. Entire groups can do the same. So can entire nations. Everyone can agree to just forget something tragic ever happened. They can scapegoat and punish anyone who reminds them of what they don't want to think about. As Russell Jacoby wrote, "society remembers less and less faster and faster... it scorns the past as antiquated while touting the present as the best. The forgetfulness itself is driven by an unshakable belief in progress."

Jacoby popularized the term social amnesia, something psychologists have spent a lot of time exploring. They describe it as the tendency "to ignore history and precedent when responding to the present or informing the future... discarded ideas are repackaged" in new forms.

These days, academics use the term collective amnesia.

In a 2001 issue of the Canadian Veterinary Journal, Craig Stephen describes collective amnesia as “the tendency of societies to recognize a new potentially catastrophic threat, react to it for a few years, and then move on.” We’ve been doing that with pretty much everything lately.

It's how we deal with climate change.

It's how we deal with pandemics.

Everyone wants to forget these things happened. They don't want to learn the lessons from these traumatic events. They want to bookend them and move on, as if they'll never happen again. When they do, everyone makes the exact same mistakes all over again.

It gets even more interesting...

Alessandra Tanesini describes the violent side of collective amnesia in Socially Extended Epistemology. As she writes, “Communities often respond to traumatic events in their histories by destroying objects that would cue memories of a past they wish to forget.” As she explains, dominant members of a group “spread memory ignorance” in order to erase mistakes they made and suppress dissent among the ranks. This memory ignorance serves as “a form of self-deception or wishful thinking in the service of self-flattery."

She calls it self-serving.

She's right.

Society engages in “fits” of collective amnesia after difficult periods of upheaval. Public figures try to suppress unfavorable memories as they rewrite narratives to make themselves look good. The public desire to forget often clashes with memory rebels who insist on voicing what really happened, especially if threats remain and injustices continue to occur.

All of this sounds familiar.

It's happening now.

All of this helps explains why people are getting triggered when they see someone wearing a mask. It explains why this doctor or that office manager won't even plug up a HEPA air purifier. They don't see these tools as signs of safety and protection. They see them as symbols of trauma.

They ignite painful memories.

There's a solution:

Michel Foucault talks about collective amnesia in his 1980 book, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. He offers a tool to fight against it.

He calls it the counter-memory.

The counter memory is “an individual's resistance against the official versions of historical continuity.” Basically, you tell your own story. You make your own historical artifacts. You share it.

Not everyone sees masks and air purifiers as symbols of trauma. I don't know about you, but my mask doesn't make me feel pain.

It makes me feel safe.

To me, a mask symbolizes intelligence and empathy. It symbolizes caution and safety. Air purifiers symbolize connection and solidarity. When I see them, I see someone who has my back.

Don't you?

Our collective amnesia will only make us more vulnerable in a world of mounting threats brought on by a burning planet. Remembering might bring pain, but it also brings wisdom. As Bina Venkataraman writes in The Optimist’s Telescope, “What remains ablaze in memory guides how we prepare for the future.” Unfortunately, western culture doesn't practice that very much. We even pass on our collective amnesia to computer models.

We encode amnesia.

Everyone seems to be realizing now that the old normal isn't coming back, even if they're desperate to hide what they're feeling behind smiling selfies and hashtags. Too many people are getting "the summer flu." Too many musicians are canceling tours and falling apart in the middle of shows. Too many vacations are getting ruined. Too many people are suddenly dying.

If we want to thrive, we have to remember.

There's no other way.